12 October 2021. The M100 Sanssouci Colloquium started with three parallel Strategic Roundtable discussions on the digital platform Zoom, introduced by an opening speech by Benjamin H. Bratton, Professor of Fine Arts, University of California, USA, on “The Revenge of the Real: Politics for a Post-Pandemic World” (the speech is avaiable as text and video here).

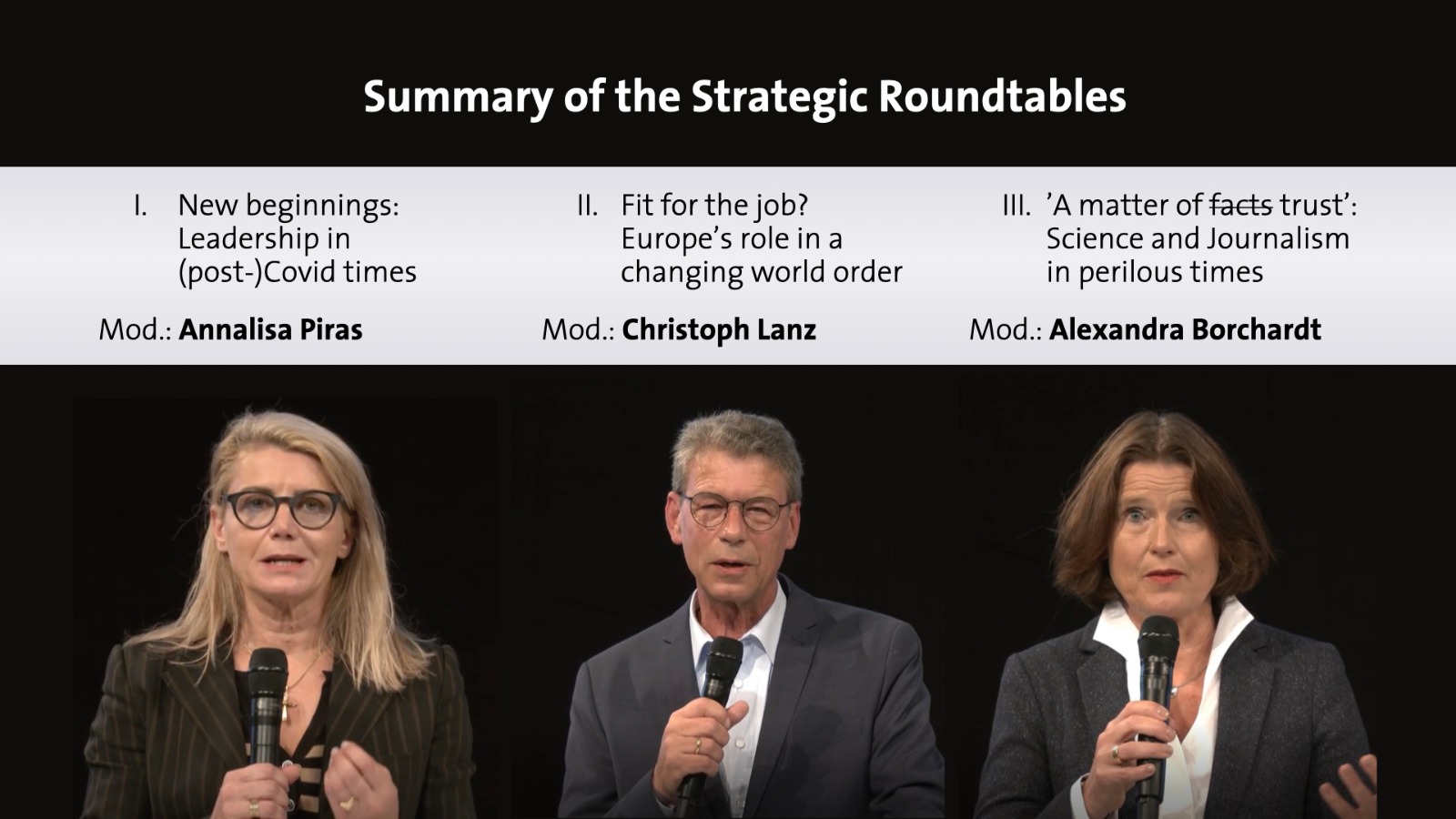

After a lively and concentrated one-hour-discussion, the three moderators presented the results of the roundtable discussions, moderated by Dr Leonard Novy, M100 Board member and director of the Institute for Media and Communication Policy in Cologne, Germany (The recording is available here on our YouTube channel). [1]

The first presenter was Annalisa Piras, journalist, filmmaker & managing director of the Wake Up Foundation. She summarised the Strategic Roundtable “New beginnings: Leadership in (post-)Covid times”, which had been introduced by an impulse by Alberto Alemanno, Jean-Monnet-Professor of European Union Law & Policy, HEC Paris, France:

“Our working group had a very challenging and ambitious subject, and we had a productive reflection on many aspects of this question,” Annalisa Piras said. “First of all, to simplify the kind of discussion we choose to use an image that was created at the beginning of the pandemic by the great Indian novelist Arundhati Roy, who reminded us that pandemics in history have always been a moment of renewal and change and a break between the old and the new. And so, we were wondering if we have to embrace this image of the COVID-19 pandemic as a portal, as a gateway to the future. What do we need to leave behind and what do we need if we want not go back to business as usual which would be, of course, the most foolish thing to do. In the discussion, we tried to imagine what we have seen through the pandemic, what was wrong and needs to belong to the past.

We have understood that one big problem of leadership almost everywhere in the world has been the tempo, the speed which react to it and adapt to these constant new challenges that the virus was bringing to leaders. We have also seen a dramatic gap between the choices of the leaders, the science, and the way the science was communicated to people. One big lesson for a new way of intending leadership is that the new leaders need to be extremely more competent and prepared not only to discern the science but also to communicate it.

And the media need to play a much bigger role in supporting this. Because most of the problems that we’ve seen, especially in the West about wearing masks or not wearing masks, were a direct consequence of the inability to communicate clearly and the inability of the media to support science during these incredibly unsettling times. In a nutshell: new leaders need to be better in understanding science and communicating it, and the media play a big role in there.

Another thing that we discussed is the disaster of the leadership, of the thinking that solutions would be national. This was a tragedy because we saw so many national disjointed initiatives. But at the same time, it brought with it an added value because as citizens all over the world have understood that national solutions don’t always work, which has resulted in a better understanding and greater awareness of the need for transnational action.

Also, we have learned through the pandemic, that working together could work. When the Joint Procurement Initiative was launched, it didn’t work at the beginning, but people understood that this is the way forward. And we have seen a model of leadership across borders that could work.

Professor Alemanno was quite rightly in his introduction, pointing at the fact that now that we’re facing one of the world’s energy crises in history and that this winter is going to be tragic for a lot of people, the idea that we have seen through the pandemic, that leaders buying things like vaccines together, could provide a model that citizens could understand of procuring energy together and again. The role of the media here is key in supporting this.

To conclude, we have seen a lot of changes and there will be even more opportunities to develop in the future. And the key is to bring back the idea of a public good that can be achieved together through nations. The media have a big role to play. One important thought is that a lot of things have changed, and we know that the business model of media is not working as it should. In this new thinking, going through this gate, we need also to bring back and rejuvenate ideas like the nature of information as a public good and the need to think of ways of funding it. Maybe the role of the state needs to come back at the center of the debate because the complexity of the changes that we leave are of such difficulty that we need more than ever qualified information. We need arbiters of truth, we need people that know that they can go somewhere where they can trust information as a public good, given out, as a public service and not as a commodity.

Christoph Lanz, Head of Board Thomson Media, presented the results of the 2nd Strategic Roundtable discussion, entitled “Fit for the job? Europe’s role in a new world order“:

“We couldn’t find a clear yes or no to the question “fit for the job”, but I would point out that we mainly agreed that economically the European Union is doing a good job”, he said. “But militarily it’s a problem. And the question, whether we should as Europe try to become strategically so autonomous that we, for example, wouldn’t need the U.S. capacities. There were some people in our panel that were in favor of that position. But the mainstream of the discussion was that we will never get to the point that we will be strategically autonomous as some might want it. And another point was the question of whether European values are outdated or not. And I would say the clear answer was: No, they are not. We should keep our faith and belief in these values and keep on propagating them. Now I ask Dr Tobias Endler from the University of Heidelberg to sum up the results of our session.”

Dr Tobias Endler: “I think that our discussion took place on two separate levels at the same time. On the first level, there was an inside-out perspective on Europe, from Greece, from Kosovo on the question of the need for institutional reform in Europe, for example getting from consensus to majority decisions. Also, the question of whether expanding the European Union at the moment is feasible and a good idea in the first place, which was debated rather heatedly. On a second level, we were looking at Europe from the outside. And that’s something that Christopher Walker from National Endowment for Democracy outlined beautifully. And we seem to reach the point where there’s a double challenge currently. Europe needs to consolidate on the inside and growing up on the outside at the same time: grow up into its global responsibility as an economic heavyweight, but still a military lightweight.

The question whether we, as Europeans, can reach strategic autonomy at all, some of the participants tend to answer that we maybe don’t have much choice. But it’s starting to think and work on that idea and maybe develop a grand strategy for Europe since the world is changing around us with the United States turning inward. Turning away from Europe towards Asia, as was said repeatedly, China making its stake, its claim, and Russia follows its own policy interests. That is why Europe should start aiming for strategic autonomy. But – and I think that was something that everybody could agree on – not against the United States, which will be foolhardy and wouldn’t even make sense geographically because there can’t be a second West.”

Christoph Lanz added that we must reform the decision-making process within the European Union. “One of the participants of the session called for majority decisions. Nevertheless, I think we all agree that there has to be reform regarding the decision-making process within the European Union. Another point was, that we allow China to divide us. Europe in general has to be very open minded to the point that others are splitting us up. And we have to check whether we are just a couple of countries that can easily be divided or whether we find a common position, especially in terms of foreign policy. And Russia is, economically seen, a minor player in the big game. And Europe is economically strong but allows Russia to pressure it.

Last but not least, we asked a participant of the M100Young European Journalists workshop from Romania, how she sees Europe and what her feelings are. And I think this is something that participants from the core European states should listen very carefully to. She said: “We are politically in deep trouble in Romania, but what we’re missing is solidarity from the European Union. And this is one point that was stressed several times in that session. So first of all, Europe has to become really united before we can face the external questions.”

Dr Alexandra Borchardt, Senior Research Associate at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, presented the results of the third Strategic Roundtable “’A matter of facts trust’: Science and Journalism in perilous times” which dealt with the relationship between science and media and the daily work in newsrooms.

She referred to the impulse by media manager Wolfgang Blau, Visiting Research Fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, who is studying the climate change coverage of newsrooms in recent years and defines it as one of the major topics for journalism these days and particularly for young audiences:

“For young audiences, climate change and global warming is the topic that they’re most interested in”, Alexandra Borchardt summed up. “We have learned from Wolfgang Blau and his research that newsrooms really need to ramp up on climate literacy. We are always talking about digital literacy and media literacy, but not enough about climate literacy, neither in the population, but not in the arts and not in newsrooms.

But this is very important because we need a common set of metrics to even communicate the basics of climate science, of climate change to the public and to discuss it with the public. And we need an agreement. For that, we need to ramp up a climate literacy in newsrooms.

We have other voices in the discussion who stressed how difficult it is for small, for local newsrooms to fulfil these requirements, because small newsrooms don’t have sufficient capacities, technically and also personally. We heard from the CEO of the Lithuanian public broadcasting, that the mostly young audiences they have are really interested in climate change, but it’s hard to find literacy. Participants also emphasised that there is a need of closer cooperation, of an alliance between scientists and journalists to ensure that journalists understand the scientific facts and are able to transport them to the public. But it also came out that science is not always certainty, it is also based on doubts, this is what science is about, and it’s a big challenge and task for media and journalists to convey this.

Another problem that was discussed is, that journalists who are reporting about climate change, very often are put in one basket with Green politics or politics from the left. It is a real issue that reporting about climate change is in the middle of a culture war. Wolfgang Blau said that he sometimes gets the question if he believes in climate change, but this is not a believe, science is an established fact. We have to develop ways to transport simple metrics to the people as we did last year in the ongoing pandemic.

The pandemic has increased trust in journalism. That shows that the debate about decreasing trust in journalism is not true overall. As the Digital News Report revealed this year, trust rose across all markets globally by six percentage points in media and it is very low in social media. The traditional media, the big brands with their newsrooms struggle every day to convince people to communicate with their audiences. They have a big plus in trust and they need to capitalize on this; only a radical minority don’t trust in media and journalists need to make the most of it.

We also discussed how a future journalism look like. And we were fortunate enough to have Ulrik Haagerup from the Constructive Institute in the group and we discussed, how can we do more constructive journalism on climate change, how can we frame the story that its constructive and talk about solutions, because if people get only catastrophe and drama in their news feed, they go into hiding, that’s a psychological effect. Ulrik said, “You have to get the facts first” and he raised some hopes and appetite for constructive journalism. He mentioned that they have organized political events in Denmark and constructive political debates which were sold out after a few hours because people are fed up with confrontation. People want constructive ways to get out of this mess, and this is what we agreed about.

[1] The text is an edited transcription of the recording.